mareas

Galería Patricia Ready

Santiago, Chile, 2023.

Galería Patricia Ready

Santiago, Chile, 2023.

sketch for mareas by Simon Jarpa.

Biombo climático. Steel, stained

glass, abalone shells.

Detrito i. Steel, gamba remains, lure, moretti glass, borosilicate glass, lead, silicone, led.

Fragata vanidosa. Fused glass,

murano glass, mirror, lead, residues.

Mollusca. Steel, blown and fused

glass, water, debris.

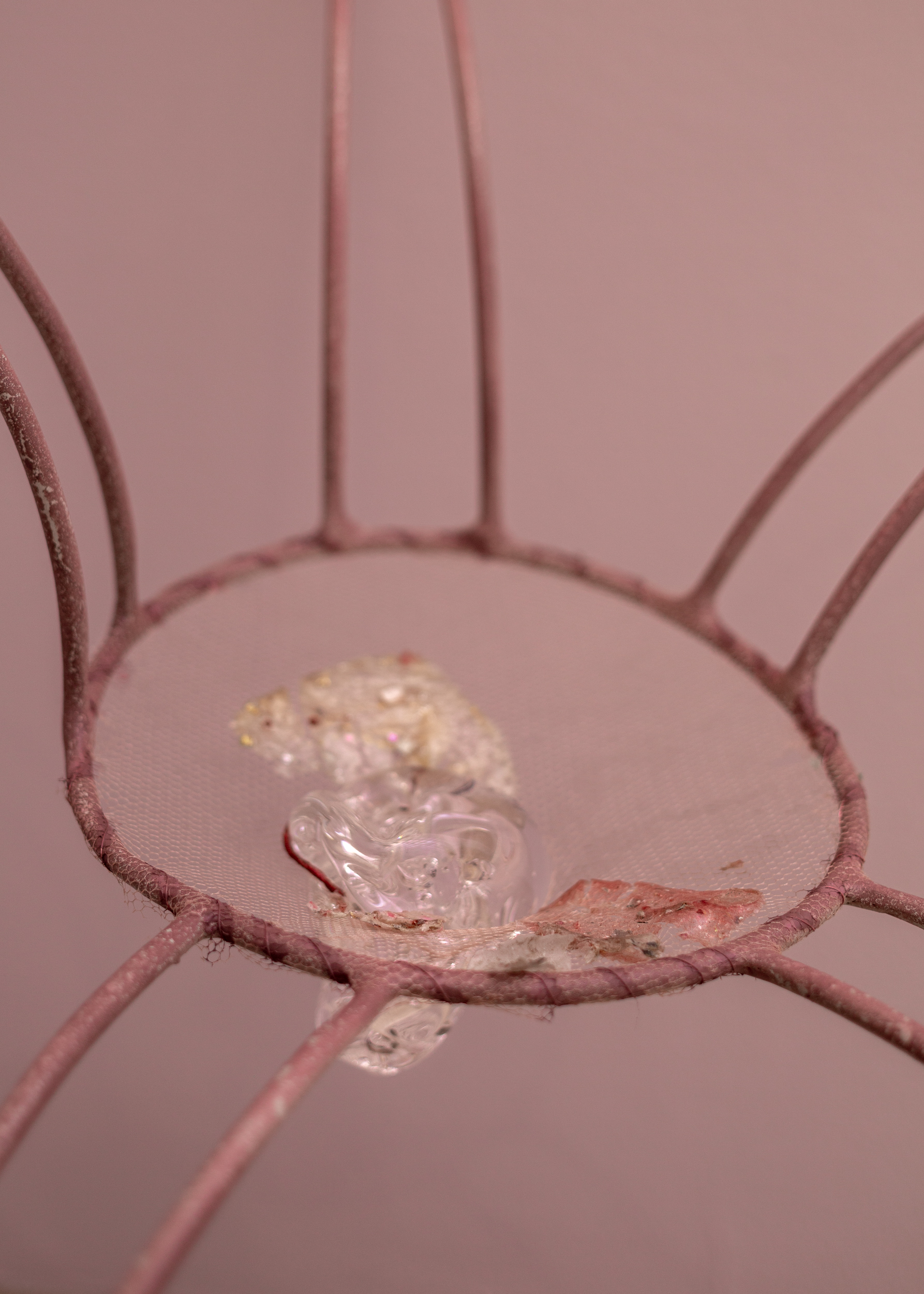

Ofiura (baby). Steel, blown glass, calcium carbonate, mesh, biofilms, pigments.

Ofiura (slippery). Steel, blown glass, calcium carbonate, mesh, biofilms, pigments. Ofiuras are a series of sculptures inspired by brittle stars.

This ocean floor dwellers floor posses a unique form of intelligence; despite being eyesless. brainless creatures, they are able to create images through a sensory system that remains mysterious to science. Covered in calcium carbonate nano-lenses, through which they form images with their entire bodies, these invertebrates feed on and synthesize organic matter, transforming the remnants that fall from the surface into new organic forms. By studying their movement, this series of sculptures draws attention to beings that not only carry out processes essential to the ecosystem but also challenge our evolutionary paradigms of knowledge and intelligence.

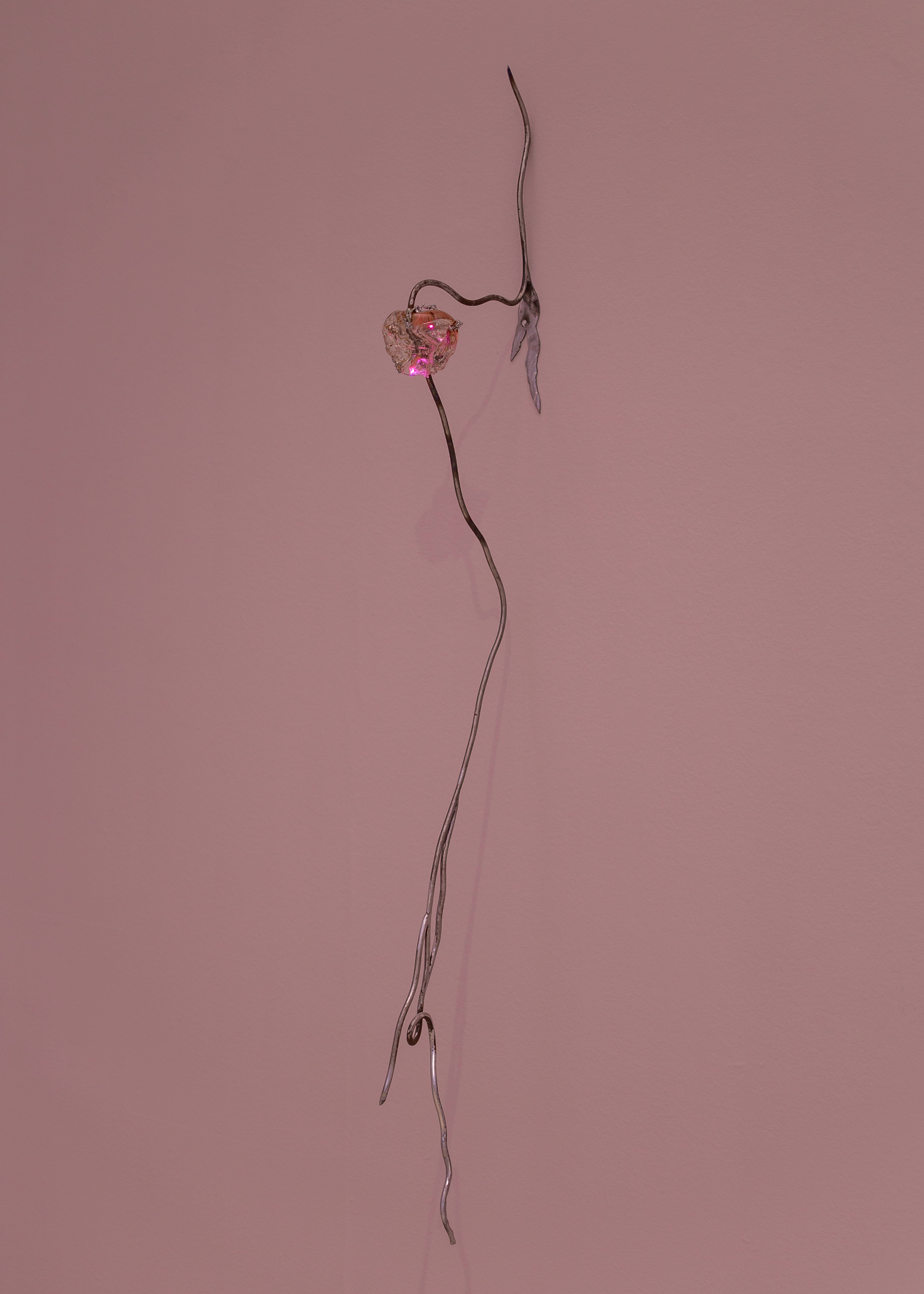

lunóxida. Steel, blown glass, lighting system.

lunóxida. Steel, blown glass, lighting system

mareas

Galería Patricia Ready, Santiago, Chile, 2023.

The ocean floor is a gigantic cemetery. From bodies to anthropogenic residues of maritime commerce and war, pleasure voyages and distressed migration, almost everything that lives or traverses this vital body of salt water accumulates on its bottom.

Even the floating communities of the pelagic zone, such as jellyfish and algae, contribute to the seabed, which far from static is alive with starfish, coral, sea urchins, crabs and microscopic organisms that feed off the organic residues that constantly pour on them. In their digestive processes, these necrophagic creatures synthesize biomass into energy. Alternatively, they metabolize toxins into nutrients or carbon dioxide, participating in the marine water filtration that produces almost half the planet’s oxygen. Finally, the scavengers of what is ecologically known as the benthic zone, or bottom habitat of the ocean, can discard these remains, which disintegrate and sediment as the tiny and singular grains of sand that make up most of the earth’s mineral geosphere.

“mareas,” ocean currents, conjures this primordial atmosphere, emulating the marine dominions that we cannot control and that, fortunately, we still don’t know well enough to fully wreck. Just like the submarine world’s appearances constantly trick us with corals that look like rocks, anemones that may turn out to be venomous flowers, and jellyfish whose touch can be fatal, “mareas” recreates our esthetic fantasy of the underwater world while it exposes it as such. The artist deconstructs the benthic zone, proposing a disjointed and dizzy (“mareada,” from seasickness) vision of this vast and vital territory. As decorator crabs, which use detritus to camouflage themselves and hide from land and ocean predators, “mareas” playfully points to the regenerative power of the submarine ecosystem.

—’Marine debris’ Exhibition text by Celeste Olalquiaga

︎ documentation images